Café Manuel, Last of the Cafes de Chinos

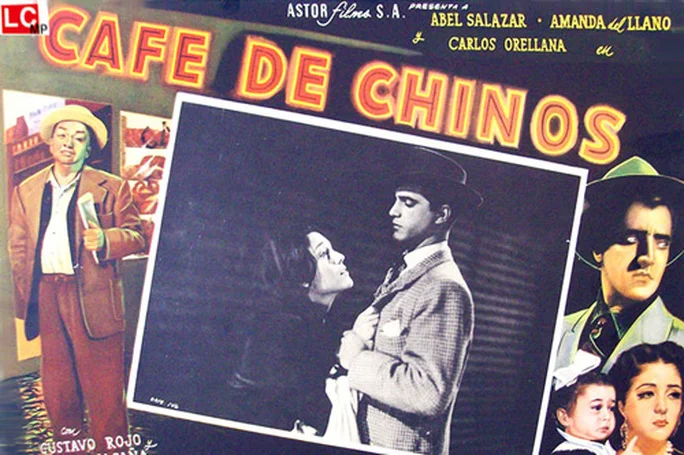

The storefront stands out from a block away, distinguished by the two red Chinese lanterns hanging over the entrance. The name is hand-lettered in an “oriental” script no longer deemed politically correct. The window on the left side of the door tempts with a display of pan dulce destined to accompany coffee. On the right, a sign proffers comida mexicana y china. Café Manuel, which opened its doors in 1934, is a typical café de chinos, a Chinese cafe. Only a few authentic ones remain, scattered throughout older neighborhoods of the city. Fondly remembered by urban Mexicans of a certain age, cafes de chinos are to Mexico what the typical coffee shop once was to the major American metropolis. They usually feature a counter and a few booths, display nominally Chinese décor, perhaps a Buddha and a Chinese calendar. Offering coffee, sweet breads, light food both Mexican and Chinese/American, many are open around the clock. They are a part of Mexican urban lore, 20th-century collective nostalgic memory. “Cafe de Chinos” is a lurid 1949 film-noir set in a typical cafe and depicts a mixed-race romance.

The Chinese have a checkered history in Mexico. While skilled workers were invited in the 19th century to build railroads, in the 1920s, Mexico’s concern over Chinese immigrants’ perceived involvement in organised crime led to the Movimiento Anti-Chino; this anti-immigrant sentiment resulted in the murder and deportation of many people of Chinese origin. Some of them, returning to a politically unstable China or a depressed U.S., eventually made their way back to Mexico. Those who remained, often intermarrying with Mexican nationals, opened laundries, import businesses and, of course, restaurants.

Entrepreneurial Chinese, already versed in American-style and Chinese “quick cooking,” opened eateries specializing in the kind of light meals they knew how to produce. Breakfasts of eggs, pancakes and pastries, accompanied by coffee served with frothy hot milk were the specialty.

Traditional Mexican offerings such as enchiladas and tamales were prepared, as were what we’d now label Chinese/American dishes like chop suey and chow mein. These eateries grew in popularity, especially in dense city centers, feeding the new breed of round-the-clock workers who needed breakfast at midnight, or dinner at 6 a.m. They reached their pinnacle of popularity in the 1940s and ’50s. In Mexico City, the streets surrounding the Zócalo were full of them: Calle Madero boasted at least four, as late as the 1960s. Then, inevitably, newer styles trumped old and these small, old-fashioned places, which often served as round the clock social centers, began to close their doors. Glitzy national chains like Vips, Sanborns and U.S.-based fast food venues replaced them. But traditions die hard, especially in a slower-paced, less-eager-to-modernize Latin America. Café Manuel hasn’t changed. It offers two set lunches, one Mexican and the other Chinese. Sweet rolls are made in-house, coffee is fresh, milk frothy and hot.

On a recent visit, I chose a menú chino, which costs about $60 pesos (about $3 USD.) It consisted of a pleasant chicken broth with bok choy, flavored with sesame oil. Next came fried rice, quickly sautéed with vegetables and egg, its smoky aroma preceding it to table. And the chop suey, the quintessential American-Chinese dish of stir-fried whatever, thickened with cornstarch, turned out to consist mostly of bean sprouts, onion and celery and a bit of chicken in a lightly sweet soy broth. It was all fresh and good, if not authentically Asian. Dolores, the longtime waitress, explained during a lunchtime lull that nowadays customers mostly order the Mexican food; “It’s cheaper,” she reminds me. Few customers are of Chinese extraction; even the cook is Mexican-born. “But we have many locals who have been coming for years and don’t expect our menu to change,” she assures me. Since the turn of the millenium, the surrounding area has become home to a new wave of Chinese immigrants and a number of traditional regional restaurants have opened their doors to serve them including a huge dim sum palace.

*Meanwhile Café Manuel carries the café de chinos tradition into the 21st century.

* Café Manuel closed in 2023 RIP