Eating out: Ecuador

Originally published in Zesterdaily.com

As in Peru, Ecuador offers myriad varieties of potatoes

Quito, Ecuador is a sleepy, provincial South American capital. Pretty, white colonial buildings in the historic center give way to drab mid-century urban sprawl, with an occasional high-rise looming like an unwelcome weed in a flowerbed. The city is surrounded by dramatically verdant hills where the metropolis suddenly ends and country begins.

Arriving at the centro histórico—UNESCO’s first World Heritage Site--I leaned out the window of our large, old-fashioned (and surprisingly cheap) room surveying the pedestrianized street below. Passers-by, most short and dark-skinned, i.e. indigenous, came and went. Many women were clad in brightly colored pleated skirts which swayed as they walked, and thin-brimmed fedora hats, the kind that are so fashionable these days amongst international hipsters. We ventured out for a jaunt, just as the sun disappeared behind the mountains. A light drizzle began to fall.

First things first, I thought – let’s scope out a place to eat. Quito’s center, I was to discover, retires like a Midwestern farm family—early. The many hole-in-the-wall lunch joints and chifa (Chinese-ish food) places serve their last meal by 4 or 5pm and turn in the towel. By the time we got around to feeling hungry, the only restaurant we could find was on the second floor of a converted colonial building, now a mini-mall. This attractive place offered Ecuadorean specialties, which, of course, I couldn’t wait to try. I ordered a bowl of locro, creamy potato soup with little else in it, and a plate of llapingachos, mashed potato cakes, served with sausage, fresh hominy and a fried egg. It was as bland as hospital food – mushy potato pancakes, squishy meat, tasteless corn. I was to eat a lot of this during the next two weeks.

I used up the whole bowl of mildly spicy, fresh tomato salsa that was thoughtfully provided. “Ok, we didn’t come for the food” we reminded ourselves. And in response to my eye-rolling and pinched expression Jim added, “It’s their comfort food.”

Hornados, Ecuador’s version of lechón asado

Things got a little better the next day at the clean, modern central market where I toured the food stalls, sampling anything that looked intriguing. The market is colorful, though not as exuberant as its Mexican counterpart. The fresh local produce includes at least a half dozen varieties of potatoes, which look earthy and fresh - yellow, white, oblong and round. There are several chilies, (here called ‘ají), and many unfamiliar tropical fruits.

Among the hot selling items are the tomate de árbol or tree tomato. Oblong and yellow/orange with a woody stem, these are not related to tomatoes at all, although the texture and flavor is similar. They’re used in salsas and sweetened fruit drinks. We tasted a variety of pulque, a drink I’d thought was exclusive to Mexico. It’s the fermented, lightly alcoholic sap of the maguey cactus, slimy, yeasty and here much sweeter than its Aztec cousin. Best of all, we found sheets of rich, dark, bitter chocolate made by the vendors themselves. Who would have thought that Ecuador produces some of the best chocolate in the world! I ended up shlepping 10 pounds home.

Encebollado

In the comedor (food stall) section of the market I tried little cakes made of mashed green plantain – pretty, exotic sounding and looking, but dull as a Latin textbook. Secos are stews of chicken or pork in a red sauce. “Tastes like Chef Boy-R-Dee”, Jim suggested. I longed for a spicy Mexican mole. I did discover, to my delight, a national dish, albeit from the coast, to which I was to become addicted. Encebollado is a fresh tuna fish and yucca soup complimented by thinly sliced onion (hence its name) tomato, cilantro, cumin and tostados, the crunchy, roasted corn kernels ubiquitous to this part of South America.

We stopped at several stands and I was full, but unsatisfied. It was only 11AM. So it was with glutton’s regret that we entered the spectacular hornado aisle. At least a dozen stands offered whole roasted pig, the creatures splayed, golden and glistening, skin crackling, their heads grinning with greasy glee. Morsels of meat, offered as come-ons as we passed by, were tender and succulent. I love roast pork in all its permutations – Mexican carnitas, Cuban lechón, Southern BBQ - and this was pig heaven.

Juana, a vendor in stand 34, explained that the animals are baked in huge communal brick ovens fueled by wood. “I need to come back tomorrow” I whined, worried that this porcine orgy would somehow disappear like a mirage. We did indeed return the next day, the smiling hogs greeting us in carnivorous anticipation. I chowed down. A plate of pulled meat is served with corn, shredded cabbage salad, and a couple of those mashed potato pancakes, which by now, were starting to grow on me. I was beginning to understand the ‘comfort food’ angle.

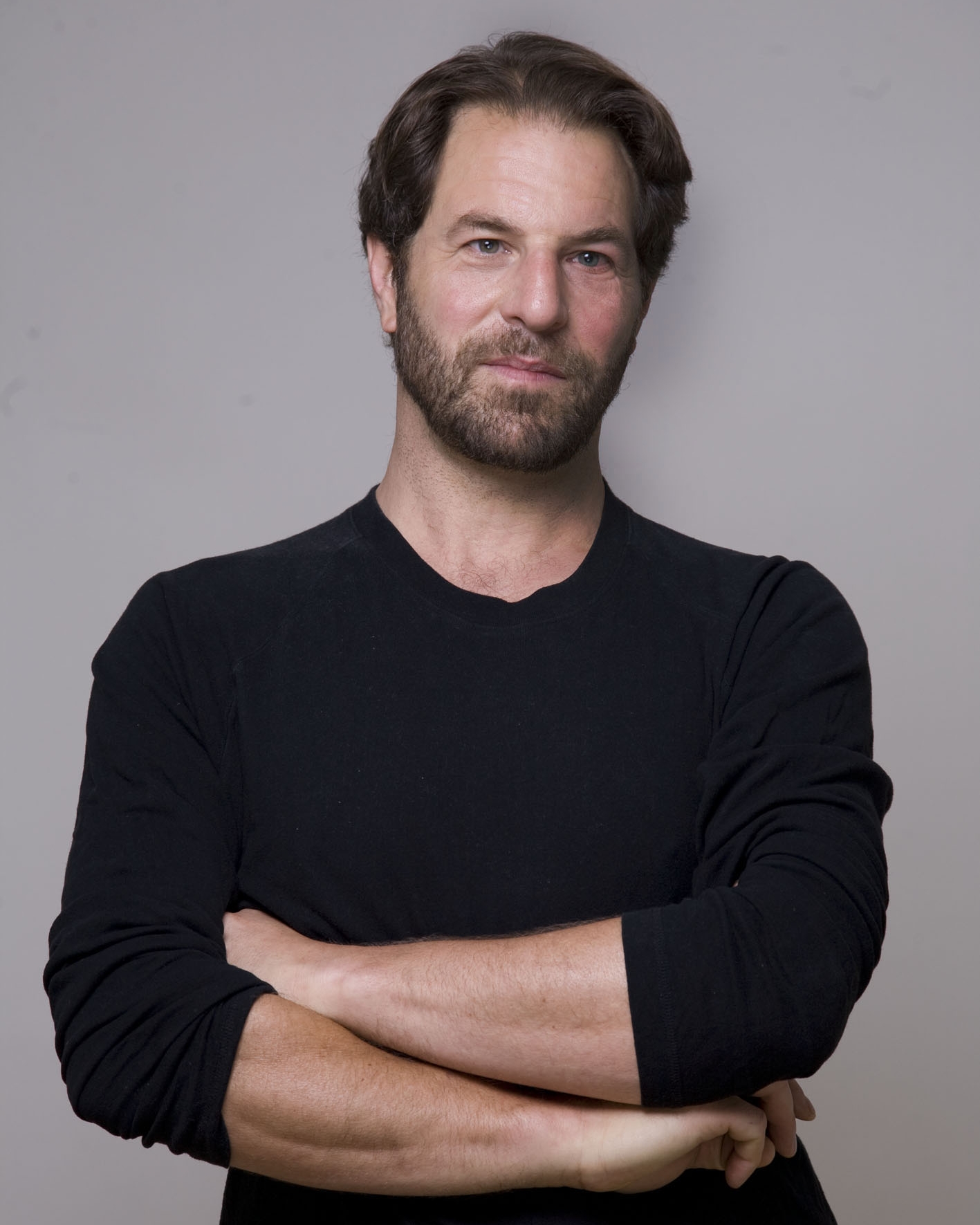

Juan Solano, chef de Tiestos

The next day, we took a short flight to the central highland city of Cuenca, a pleasantly laid back and walkable colonial town whose cobbled streets are lined with ornate turn of the 20th century stuccoed low-rise buildings. While I enjoyed walking around and chilling out here, the food scene did not look promising. The variety of market and restaurant choices was smaller than Quito– how much pork can you eat, after all? That was soon to change when I stumbled upon perhaps the best restaurant in Ecuador, and met a chef who provided an enlightening insight into Ecuadorean cuisine.

On a tip from a fellow traveler, we decided to try out Tiestos, which promised gastronomía Ecuatoriana. On a quiet Sunday morning we strolled over to the restaurant, located a few blocks from our hotel. I knocked on the bolted rustic door and was admitted by a large, jovial man clad in splattered apron and work-worn bandana. He turned out to be chef/owner Juan Solano. On examining my business card, he told me that he would like to fix us a special meal so we could taste everything– an offer I couldn’t refuse.

Chef Solano is only 38 but has deep roots in his hometown of Cuenca that go back centuries. "The street we're on, Juan Jaramillo, is named after a relative of mine,” he pointed out. "My family began with a little tienda (neighborhood grocery store) decades ago. My mother started making ice cream to sell to the kids after school and it was such a success that it became the focus of her business. Everybody would say, ‘let's go down to the tienda for ice cream’, so they named it Heladeria La Tienda –‘Ice Cream Shop ‘The Store’."

Juan studied cooking at Ecuador’s best-known culinary school where he learned primarily European cuisine. “I didn’t see why I couldn’t present Ecuadorean recipes in a sophisticated and creative way” he explained. So, two years ago, Tiestos, a family restaurant where the chef’s wife, Laura prepares the desserts, was born. “My family works in the restaurant so I can keep track of them”, he proudly explains. The word tiesto is a dated Castilian term for the common ceramic plate still used for cooking in most kitchens here. Main dishes are served on artisanally handcrafted versions of this plate. The dining room, of rustic stucco set with hand-hewn tavern tables, is warm and welcoming.

Salsas and condiments at Tiestos

The dishes offered are local– based on Spanish and indigenous Andean traditions. The chef adds touches of his own; an Argentine chimichurri, or an Indian influenced fruit chutney perhaps. But all utilize ingredients native to the area. Upon sitting down we were presented with eight little dishes of condiments that reminded me of the way Korean kim chi are served. These included roasted potatoes, several pickled onion with chilies, some fruity salsas and one curious tomatoey and mildly picante sauce, which turned out to be made from the aforementioned tomate de arbol.

Appetizers included a dense, doughy tamal that bore little resemblance to the Mexican version; its ruddy masa is made of ground hominy and scented with clove and achiote, wrapped in a leaf called achila, then steamed – its flavor was satisfyingly complex and soulful. We moved on to the previously predictable locro (the creamy potato soup, here done with chancha, a typical yellow potato). It was subtly fragrant with hints of ground spices such as nutmeg and cinnamon.

un tiesto de camarones

But the stars of the show arrived when the curtain went up on the tiestos themselves: meats and fish broiled/roasted tandoori style on the aforementioned flat ceramic dishes. These beautiful hand-wrought plates (of course I lugged a few home), blackened from constant baking over wood-fueled stoves, are brought to the table, sizzling and smoking.

Our first dish consisted of enormous, succulent shrimp, bathed and broiled in flavorful, farmyard butter. Simple, fine ingredients were well manipulated. The butter and smoke permeated the meat--perfection itself. Next came the lomo fino a la crema, falling-apart tenderloin of beef, bathed in a melted cheese sauce. This was a local variation of solomillo al cabrales, the famous blue-cheese enveloped glutton-fest from northern Spain. We didn’t have room for the curried chicken Juan offered but I smelled one as it sailed by – I almost could have been talked into it. The food here was rich and heartwarming; country cooking at it’s best. While dishes ranged from indigenous Andine folk fare (the tamales) to Spanish colonial adaptations (the meat) all were done with respect to local as well as international tradition. I treasure the casual roughness of this kind of unfussy cooking.

herb vendor, Cuenca

The next morning, we jumped at an invitation to go shopping with chef Solano, who was kind enough to invite us to accompany him to the sprawling mercado de abastos where he buys his produce for the week. As the early morning fog lifted, we drove out to San Joaquin, an outlying community known as the ‘garden of Cuenca’. Juan has shopped here since childhood and knows the names of many of the vendors, who come from the surrounding countryside to sell their produce. We breakfasted on tamales, a long skinny earthy one called a chibil and a round, delicately flavored timbulo, washing them down with a slimy, bitterly medicinal drink called pinazo con boldo. In one aisle, we observed a stout, hat clad indigenous woman performing a limpia or spiritual cleansing, on a young girl: she swatted the poor frightened creature with leaves and waved burning incense all about. The girl sat patiently for a time and finally burst into tears. With a hint of gringo cynicism we asked Juan about it. “When my daughter was 4 years old she got very sick and the doctors told us she would not survive. A curandera saved her life. Of course it works!” He assured us.

The chef at work

Chef Solano shopped quickly but carefully, checking the quality of each herb or vegetable, observing what was freshest in the market, inventing his menu as he went along. Finally, when all was selected and heaped on a cart, it was was drawn to the parking area by a small indigenous woman. We returned to town. I was content knowing that later that day I would see the booty refashioned as great food.

It’s comforting to discover that even in a small country not known for it’s cooking, there are culinary treasures to be discovered. Ecuador lives in the shadow of the ever more gastronomically popular Peru. Perhaps the ‘taking back and celebrating’ of one’s cultural and heritage is a global phenomena. But as long as there are Chef Solanos around, they can send all the Starbuck’s they want.